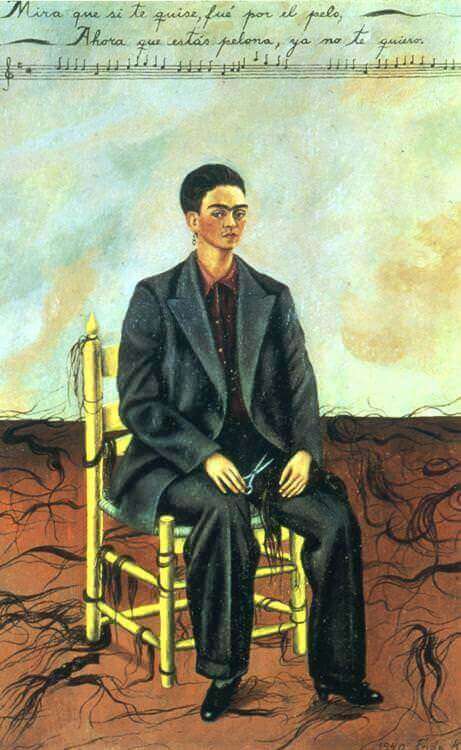

In 2004 a remarkable trove of personal items belonging to Frida Kahlo was brought to light at her lifelong home, La Casa Azul (the Blue House) in Mexico City. Locked away following her death in 1954 at the instruction of her husband, Diego Rivera, these materials are now on view here in San Francisco, a city that played a significant role in shaping Kahlo’s self-fashioned identity and launching her artistic path.

Born in 1907, Kahlo lived her formative years against the backdrop of the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920) and the cultural renaissance that followed. These momentous events shaped her enduring commitment to Mexico and her communist worldview. She took up painting in 1925 while recuperating from a serious traffic accident that resulted in lifelong medical complications, multiple disabilities, and chronic pain. Although overshadowed by Rivera during her lifetime, today Kahlo is internationally renowned as a cultural icon and as one of the most significant artists of the twentieth century.

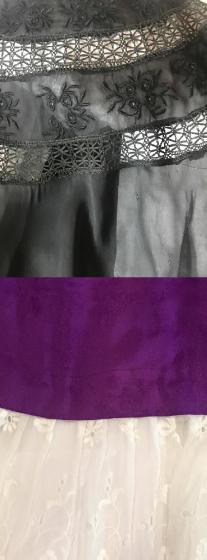

This exhibition provides a rare opportunity to examine Kahlo’s diverse modes of creativity side by side. It presents poignant items from the Casa Azul trove—newly discovered photographs and drawings, medical corsets, accessories, and vibrant garments—alongside artworks that span Kahlo’s entire adult life. The show illuminates Kahlo’s intimate world and the ways in which politics, gender, disability, and national identity informed her life, her style, and her bold, uncompromising art.

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving is guest-curated by Circe Henestrosa, independent fashion curator and head of the School of Fashion at LASALLE College of the Arts Singapore, with Gannit Ankori, professor of art history and theory at Brandeis University, as advising curator. Hillary Olcott, associate curator of the arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, is coordinating curator for the de Young.